This post was originally published on this site

A crowd of faithful gathered on a concrete wharf as His Eminence Archbishop Elpidophoros of America offered an Agiasmos, or Blessing of the Water, over a fleet of sponge and fishing boats.

At the end of the wharf, Archbishop Elpidophoros boarded a Kaiki, or a Greek-style work boat, that has been captained for 30 years by a swarthy-skinned fisherman and sponge-diver named Anastasios “Tasso” Karastinos, dashing the blessed water onto the deck of the ship and about the narrow quarters in which Tasso has lived since Hurricane Milton damaged his home ashore in 2024.

It was the eve of Epiphany. The next day, the Great Blessing of the Waters would have 74 young men jumping from boats, onlookers of all backgrounds watching as the boys thrashed through the cold and murky January waters in search of a sinking cross. The one who retrieves it gains a yearlong blessing.

Tasso’s grandson, Athos, would be the one to retrieve this cross this year. Athos’s father, Anesti, also retrieved the cross, making Tasso the local patriarch of blessed sons.

The Great Feast of Epiphany, or Theophany, is among the most sacred and celebrated feast days of the Orthodox calendar, commemorating the Baptism of Jesus Christ in the River Jordan by Saint John the Baptist and the divine revelation of the Holy Trinity. The feast celebrates the sanctification of creation and the beginning of Christ’s ministry.

“We cast the cross into these waters to symbolize our commitment to bring the message –the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ–to every soul, to every corner of the globe,” Archbishop Elpidophoros stated on a platform above the Spring Bayou before throwing the pearly cross glowing in the midday light.“For just as water pervades all life on our planet, so the Word of God – the Logos of His love – is infused within every aspect of the created order, which only awaits to awaken to its divine presence in the fullness of time.”

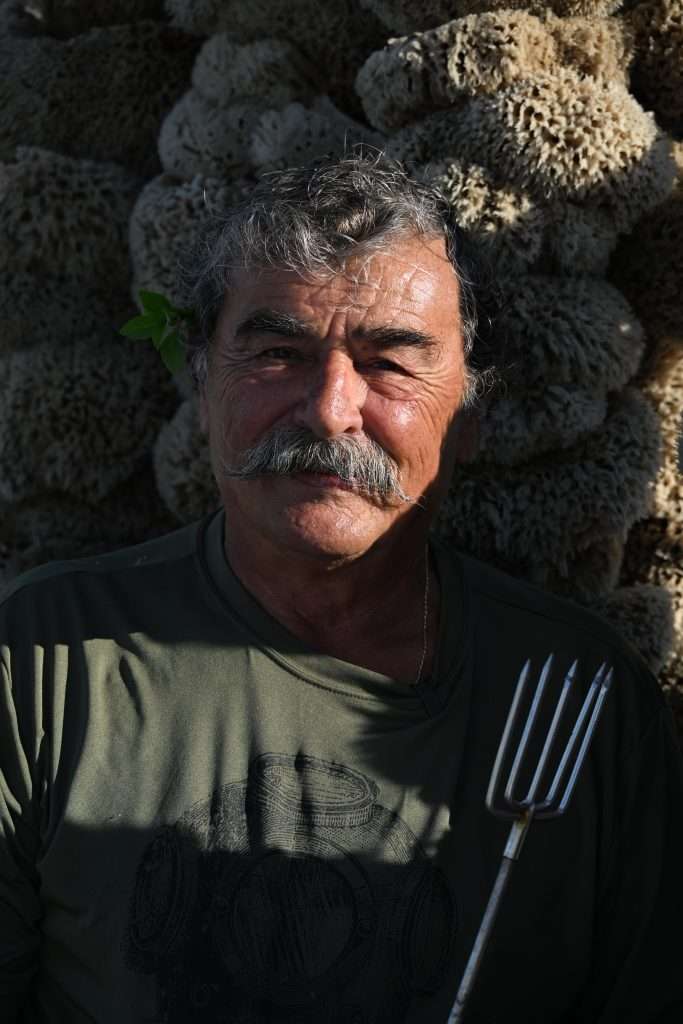

After the Agiasmo, Tasso wore a stem of basil from the blessing behind his ear and a green shirt depicting the copper-cage helmet first-era divers would don to descend into the ocean deep. He has lived in Tarpon Springs since 1972, and it was here that he built his first boat and began a career that would take him far from the Sponge Docks and into the depths of Florida’s coastal shelf.

“When a sponge-diver goes down, he goes down forever,” Tasso said aboard the Anastasi, which he built in 1991. “Every time I hit the bottom when I’m diving, I get on my knees and I pray, because I don’t know if I’ll make it back up again.”

Every diver, Tasso says, has “risks behind his head.” Tasso speaks about finding his faith where it is empty and quiet—whether it is in an emptier church, or on the sea floor.

“You go down, you don’t know what can happen to you,” Tasso said. His own brother died deep-diving in Greece, and Tasso acknowledges he himself has nearly drowned under the immense weight of the ocean. At the levels descended when deep-sea fishing, or sponge-diving, the pressure can put divers to sleep. A diver cannot ascend from these depths if their regulator fails.

Unceasing prayer is a routine part of Tasso’s diving, just as is dragging an 800-foot air hose through the depths of the Gulf of Mexico. In some instances, prayer might act as proof of having breath.

“I know the pain, I know the feeling,” Tasso said. “You have to be asking for forgiveness from God, for whatever you have done. Then, you must ask for your protection, with all your heart and all your mind.”

Tasso, who has been deep-diving since he was a child, was part of a wave of Greek immigrants who brought advanced maritime and diving techniques to Florida, propagating what has become the world-renowned sponge dive and fishery known as Tarpon Springs.

Tasso’s quarters on the Anastasi are narrow. The wooden dash of the boat is patinated and sunbleached from decades of maneuvers up and down the west coast of Florida. Among the clutter is a Galanólefki (‘Blue-and-White,’ or Greek flag) that hangs from the ceiling by a clothespin; a wooden cross is mounted on a blue communications wire. Iconography is pinned to his walls behind electronic equipment—a sacred background for the touchy equipment and wires which have often acted as a lifeline for the sailor.

“If you’re a pirate like me, it’s good enough,” Tasso said.

Trips to sponge-diving locations can last 20 days or more—no cell connection, and miles from shore. “I shut my engine off, and you can hear your heartbeat,” Tasso said.

“Everybody loves the ocean by looking at the top, but if you get into it and you work on the bottoms as much as I do, then you become one with the ocean,” Tasso said. “Then you see the life of the ocean.”

“It’s a huge blessing,” Athos said upon retrieving the cross from Spring Bayou. “That’s all I can say.”

The post The Archbishop blessed his boat. Then, his grandson retrieved the cross from Spring Bayou. appeared first on Orthodox Observer.