This post was originally published on this site

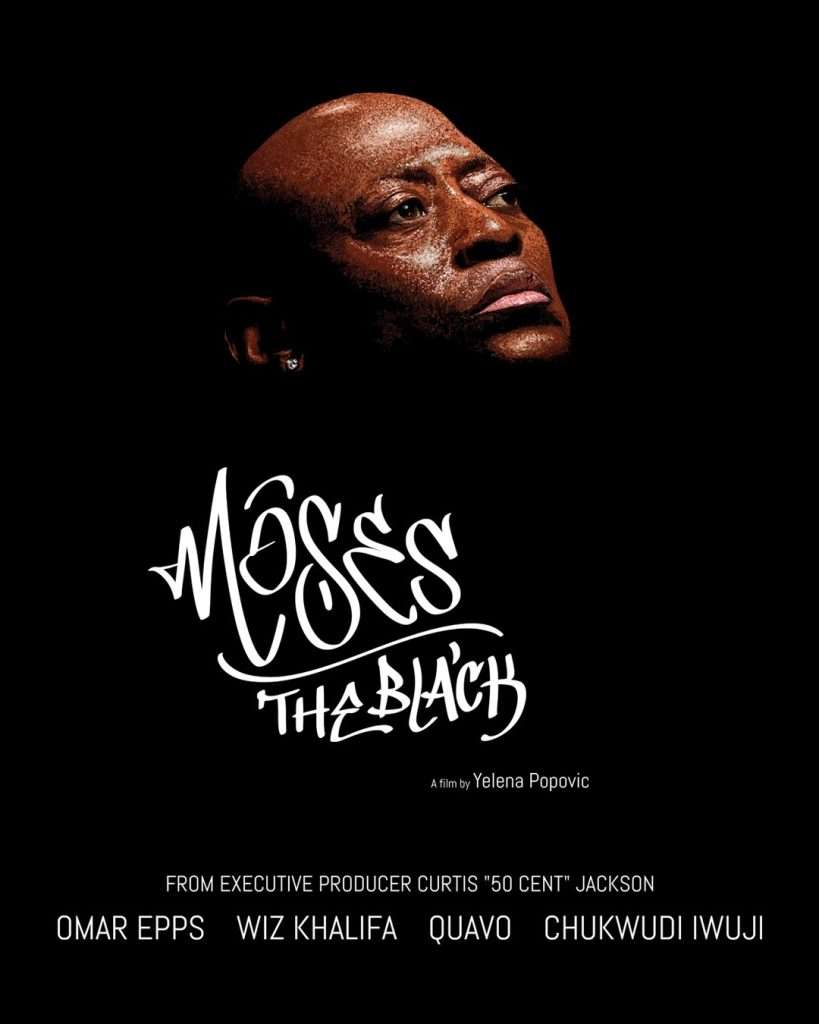

Reserve tickets for Moses the Black, starring Omar Epps, Wiz Khalifa and Quavo here. The movie is scheduled for release to theaters nationwide January 30.

This interview explores the filmmaker’s motivation and approach to creating a feature film about St. Moses the Black, a former gang leader in 4th-century Egypt who repented and became a revered Desert Father and martyr.

The film unravels deeply layered themes of repentance, redemption, and faith, aiming to inspire those feeling trapped in destructive lifestyles. The filmmaker, Yelena Popovich, emphasizes in this interview the film’s gritty realism and refusal to offer a simplistic view of redemption. The film’s narrative and pacing include quiet moments, but expand instantaneously to reveal the often violent social complexities of inner-city Chicago.

While working on the film, Popovich ingratiated herself with community leaders impacted by gang violence—saying she only took script-writing advice from the ex-gangsters she met during the making of the film. Much of the acting and dialogue performed by rapstars Wiz Khalifa (playing 2wo-3ree) and Quavo (playing Straw) was elevated by improvisations.

Popovich calls herself a “hardcore storyteller,” obedient to truth and a mode of filmmaking in Orthodoxy that confronts sin personally, and bars no holds on the viewers emotions as they follow Malik (Omar Epps) on his journey from prison to reverence.

SA: I know you’ve talked about this in previous interviews, could you please tell us where the idea for a Moses the Black feature film began?

YP: I was already, I think I have to answer it this way because it was definitely connected to Man of God in a way that before I did Man of God, before I read about Saint Nektarios [of Aegina] in 2012, I never thought I was going to make a film about a saint. You know, that’s an honest thing. So I think that even though I already finished the script and it was before I was in the production of Man of God, it was around 2018. I knew about his [St. Moses the Black’s] story, but then at one point, because I like to reread the stories of saints, for personal reasons, I love the stories. Obviously, the stories of saints are very inspiring, encouraging, very beautiful. And I read again about him. At that particular moment, it struck a chord in me that was similar to what I felt when I read about St. Nektarios, probably because I was already about to embark on making a film.

I thought, well, how about also trying to make a film about St. Moses, because this story is incredible. It’s a story of repentance. He’s a saint of repentance. He’s one of the holy desert fathers that people don’t typically recognize.

Even though at the beginning of his life he was a very brutal, violent gang leader in the land of Egypt. And what’s interesting about him is like not only that he repented of his deeds and changed, but he became a very well-respected desert father. He was the disciple of St. Macarius of Egypt. If you read in Philokalia texts, he’s very often quoted and he’s very well respected. So he’s one of the desert fathers and anybody who knows about it knows how significant that is.

To go from a gang leader to not only a man who has repented and changed his life, but to become like a holy father, a martyr for Christ, to me, is really fascinating.

What really struck a chord in me was the way he died. When I read about the fact that he was an abbot when he was 74 years old, he had at that time about 70 disciples—and many years before that, he had 70 gang members. Now he had 70 disciples. Some of which were actually ex-gang members. He managed to transform by his example, even some of his former gang members.

So he was there in the desert and he saw that the robbers were coming to raid the monastery, which was something that was happening a lot at that time. And people say that because of the life of St. Moses and because of the way he died, this was the fourth century. At the time, monasteries didn’t have big structures. The monks, during the time of St. Anthony the Great, mainly lived in the caves. And there were, you know, if there was a chapel, it was something very, very primitive and small. So they didn’t have any walls, anything to be protected by. And they say that because of the martyrdom of St. Moses the Black … they began to build walls around for that reason, to protect monasteries from intruders.

So to go back to the story, what really struck me was that he got up and told everybody that the robbers were coming and that they were going to kill everybody. He asked everyone to leave. His disciples wondered what would happen to him, and he told them plainly that he had waited for that moment all his life—that he had prayed for it and that he wanted to glorify his Lord and Savior by his death. And the words of the Lord say, “Who takes the sword must die by the sword.”

And to me, that was—I mean, you talk about real repentance, something very deep about it. It doesn’t mean that we all have to desire to be martyrs; that’s not the point of this. But to me, it just showed what kind of man he was, how deep he was, how righteous he was—that he simply… I mean, to be honest, he had evaded the death penalty because he was a man with a bounty on his head after he killed a government official. That’s where he ended up hiding around the monastery at first, to run away.

But then that change happened precisely at that place, when God spoke to his heart and he realized what kind of danger his soul was in. He asked the monks to accept him into the monastery—not to hide him from the authorities or even from death, but to help him save his soul.

So somewhere—and this is just my opinion, maybe through researching and praying to him every day—I felt at one point, and I don’t know why, it just came out of nowhere, that it’s almost as if he knew he had evaded the death penalty for what he had done. And by law, at the time, if you became a monk—if you decided to go to a monastery—you would not be charged for something like that.

Just like we think about St. Paul, when he was falsely accused of many things that he hadn’t done, right? He said something like, “If I did something that’s deserving of death, I would gladly give myself up, but I didn’t do anything.” But in this sense, St. Moses knew what he had done, and he felt somewhere deep in his soul that it was a righteous way to go.

And this is something that really, really struck a chord with me. I felt that his story and his example could resonate with a lot of people, and that this kind of story of redemption could resonate—potentially help people.

Even with Man of God, I did it for very similar reasons, even though it’s an entirely different story. I would say that often, when people ask me why I did it, I say I did it to help those—hopefully—who suffer the most. And in this case, it’s hopefully to help those who feel they are prisoners of destruction, of this terrible lifestyle that they feel they either cannot get out of, or they don’t believe that there is repentance. They don’t believe that God is merciful enough to give them another chance. So I think this is for people—they don’t have to be in gangs or suffer from addictions—for any kind of bondage. And we all have something; I mean, I certainly do.

And when I sat down to write the script—and this was very important—I asked myself, “What am I going to write about? Okay, I’m writing about St. Moses the Black, but…” This was after I figured out the story about Chicago and everything. I asked myself, “What is this? Why is this so personal to me?” And I realized that, for me, it was about getting out.

And when I wrote that down—get out—I put that on the side of my notebook, and that’s what guided me through every scene of this film. And I wanted, hopefully, to transmit that to the audience: that there is always a way out. If you feel stuck, if you feel your life is meaningless, if you feel that you don’t have a life, that you don’t have a voice, that it’s like you’ve tried everything, and somehow you feel like you can’t find a way—that there is a way.

SA: I’m reminded of the ministries that we cover here at the Orthodox Observer, such as the Orthodox Christian Prison Ministry, which invites people to explore Christianity in prisons, the ways to give the destitute, the hopeless according to society, a way to meaning, right? A path toward a meaningful, fulfilling, Christ-like existence. And so I think that the film does a very good job in inviting this reality.

The film brings to Orthodox Christian filmmaking a taste of the grittiness of social situations which seem to the people in them inescapable. For the sake of not spoiling the film, I will not mention how the film ends, but it’s an ending which might leave the audience wanting resolution. It’s an ending which requires faith—and that’s what I like about the film so much—yet so many people would like salvation in this lifetime. The film doesn’t give us that, and I’d like to explore this storytelling decision.

YP: It requires faith, and he made the ultimate sacrifice—for his brothers, not just the ones that were left behind, but also for those that are gone and maybe did not know better. So to me, that’s powerful. You see, it’s like he made that choice—that was the choice that he… it was his freedom.

And I want to say something. I’ve done a lot of research. As you can imagine, I’ve spoken to a lot of people. There were—or still are—some who have affiliation with gangs, with that kind of lifestyle.

When I spoke specifically to Father Paul Abernathy. I don’t know if you’ve heard about him. He is this incredible pastor who serves at the Antiochian Church of St. Moses the Black in Pittsburgh, in the Hill District. They have this Neighborhood Resilience Program, and what they do, actually, is that former gang members who have already abandoned that lifestyle, engage at least three times a week in preventing gang violence.

And this is very dangerous work because, A, the only way that somebody can prevent gang violence or convince someone to change their lifestyle at that point is through an ex–gang member. They would not listen to somebody who is not, because there has to be someone they feel understands them—someone who is not judging them, not coming from that place—someone who has lived the same lifestyle.

So there’s one particular gentleman that I spoke to before I met my main consultant, Reginald Akinberry Sr., in Chicago. Before that, I had spoken to some people at the church. Some of them are Orthodox, some of them are not—it doesn’t matter. They work for the Neighborhood Resilience Program.

But this particular gentleman I spoke to—I had already told him that I had an outline in my mind, and I was discussing a few things with him. Later on, Father Paul told me, because of this particular thing that you’re asking me about—why this kind of ending, which you like—he said to me, “You know what’s interesting, Elena? You’re telling me how you want to tell this story, but that’s really going to resonate with people inside of this kind of lifestyle.”

Because, my friend—this particular gentleman—said, “I’ve asked him many times: I see you go every two or three days to prevent gang violence. And I can see that he doesn’t only go there, but he kind of puts himself in harm’s way. And I asked him, ‘Why do you do it like that? Why are you not being a little more cautious?’”

And the answer to the father was that sometimes it’s not enough just to say, “I’m sorry.” Do you see that? That’s it. That is that. That’s the keynote that you’re talking about.

Then there was another incident. This was actually at a monastery in Serbia. There is a place where they house a lot of addicts or ex–gang members, and they really have a program for that. It’s a monastery dedicated to the Archangels—Archangel Michael. And one of the monks was an ex—well, it doesn’t say exactly what he was doing, but he was in that kind of world.

And when I told him a little bit about the story—because I was doing a lot of research on it again—when I struck a chord with that particular element of him sacrificing and dying at the end, willingly, he said to me, “You know what’s so interesting, Elena?” He said that when he was in Zemun—which is a place where there were a lot of gangs—he remembered one of the leaders at that point. One of the leaders who changed, became very Christian, and would go around grabbing kids off the street and telling them not to be in that world.

He told my friend, who is a monk today—he told him one day, he said, “You know, you see that corner over there? I’m going to die there.”

So his mom—the father told me—I was disturbed. I said, “Why?” And he kept saying that to me, many, many times. And I asked him, “Why are you saying that? And why do you have a smile on your face when you say something like this to me?” Because he’s not happy about that. And he told him, “Come on. You know what I’ve done in my life. It just would not be fair for me to go in peace.”

I mean, this is what I’m saying. This particular storyline will speak very closely to the hearts of people who have been in gangs, who have done things they’re not proud of. Because for the majority of them, the hardest thing—according to numerous pastors I spoke with—when they would come and seek repentance, the hardest thing they would deal with was the belief that they could be forgiven.

This was the biggest challenge, because they simply could not believe: How can I be forgiven after everything I’ve done? And that’s why I have chosen to tell a really truthful story—a story that will really speak to people that have experienced that world and understand that world, because I think that this really is for them primarily. Yeah. And obviously then for everybody else, because we are all sinners—first me, and then, you know, I can say that for myself. It’s helped me, but I think that I would like to reach, as you say, people that really need help, light, and hope—people who maybe are forgotten and, again, feel there’s no way out.

And I think that because it’s so truthful, it’s so real—it’s not a fairy tale. It’s not a fairy-tale ending. You can’t have that with… you see, I’m a little bit of a—I’m kind of a hardcore storyteller. I am a student, I would say, of Dostoyevsky. If you read his writings, you would see that he would always show the ugly truth of our world, of society, of the human soul.

And yet, there is light at the end of the tunnel. And this is something that I like doing with my work, and I believe that I’ve done that here. But again, I don’t think I could do justice to St. Moses the Black if I tell a story of a gangster that’s cute. It’s just not going to… it would not resonate in the same way. It wouldn’t be real.

SA: I definitely agree. I think that you undertook a very daring endeavor, given that the content matter of it could be very easily…There are pitfalls to this kind of story, right?

“A gangland flick,” one reviewer called it. I don’t really see it as a gangland flick … The film does so much more. I think people can get lost in the film’s upfront confrontations with violence or the crude nature of the language, given the overall lifestyle and experiences it presents is one that the Orthodox world doesn’t particularly relate to. I think you took this film and took the suffering of the Black American youth seriously. And there are serious answers within Orthodoxy for this kind of suffering.

The film can be loud. There were shootouts. But there was also a panic attack. That was a quiet scene. There are serious moments of reflection. There’s a very meditative tone to the film that I appreciated. How did you decide to say things in this film without “saying” them? Because it seems to me that Malik’s (the film’s protagonist, played by Omar Epps) spiritual awakening happens before the film even begins.

YP: Omar Epps and I worked very closely after—obviously—the script was finished. I also did some rewrites on this character and a few things, because he’s just this incredible character—an incredibly talented, dedicated actor who’s not going to do something just to do it. He really dived into this with his full heart and soul, so it meant a lot to him. We worked very closely, and that was a discussion we had. We both agreed—when I was writing the script and he picked up on it—that the conversion had to have started.

Yeah, in the prison—yes. It doesn’t mean that he completely converted, no. But the things that happen in prison—because prison is a place where, especially if you’re in solitary confinement, or if you’re spending a lot of time by yourself—you’re forced to look at yourself. And it’s there that you can, as you know yourself, in the Psalms it says, “Be still and know that I am God.”

And that “be still,” you know, in our society today, is a very difficult place to find. But in prison, you’re forced to be still, whether you like it or not. So this is very likely—this is how, when I wrote it—that he… and later on, when he talks about it, he felt this peace. He said that the only time he felt this unusual peace was when it was the most difficult—when he thought he was not going to make it, right?

And probably it happened in prison—that he knew that there is something out there, that there is God, even if he was trying to reject that thought or didn’t think much about it. But being in prison, you’re faced with that question, because you’re forced to look at yourself in a very, very deep way. So something must have happened already, where he was already thinking about it.

So, as you know, I chose a storyline that not only a gang member can relate to, but a storyline that anybody can relate to. Basically, it was a storyline of revenge—revenging his own son, his own best friend. That’s something you don’t have to be a gang person to relate to. There are a lot of people—if something terrible has happened to someone—a person might be inclined toward revenge, right? That’s something regular people can relate to.

He took his inclination to avenge his best friend. You know, everyone looks for redemption in his lifetime—exactly. So he’s coming out not to… as you can notice, even his friend is there saying, “We have business to run,” and all that. He’s coming out with only one thought in his mind: to avenge the death of his closest friend.

And so, yes, that’s not a Christian way, right? But you can’t say that he was just coming out to kill people for fun. That wasn’t the case with his character. So yes, he is a little deeper than that. And I felt like I had to choose a character like that—one where there was potential in his heart and soul—so that once the seed is planted, he can understand the truth and then completely move toward that truth.

Because I felt this was the story of St. Moses. St. Moses, even though he was a merciless killer and a robber and all of that, there must have been something in him that was not lukewarm. When he was a killer, he was a killer all the way. In the same way, once he realized God existed and was offering him mercy, he abandoned that lifestyle forever, and he never looked back.

SA: How would you respond to the people who are disturbed by the scenes of graphic violence and vulgar language of the film?

YP: If you’re on the path of doing those things and you’re not very uncomfortable hearing or seeing any of that—which is a good path to be on—you don’t need to see a movie like this for any spiritual benefit, because you’re already on a good path. This is the film for people that need that—that God loves as much as He loves all of us who are trying to live a spiritual life—but He wants all of us to be saved.

This is the film for people who should and would like to change their ways, but don’t know how. This is something that’s geared toward people—the same work that St. Moses the Black wants to do.

You know, I really felt strongly about this, because I was wrestling for many, many months—maybe even a couple of years—with the story of St. Moses in the fourth century. It was going to be a film that would have so much impact nowadays, with people that really need it.

The post Yelena Popovich’s ‘Moses the Black’ knows redemption is no fairy-tale appeared first on Orthodox Observer.