This post was originally published on this site

How does a saint become recognized as a saint? Seeking to answer this question, Char Mansfield and Byron Walker are working to recover the memory of a woman whose holiness was once praised by Christ himself.

Their project, grounded in scholarship, reverence, and deep respect for the Orthodox tradition, seeks to recognize a figure who has never been given formal canonization–a woman whom they call “Kenosia.”

This woman is the poor widow from the Gospels of Mark 12 and Luke 21, who offered two small copper coins to the temple treasury. Though seemingly a small gift, it was absolutely everything she had. Her offering drew the attention of Jesus, who pointed her out to his disciples:

“Assuredly, I say to you that this poor widow has put in more than all those who have given to the treasury; for they all put in out of their abundance, but she out of her poverty put in all that she had, her whole livelihood.”

Mark 12:43-44

Mansfield and Walker approach the project with extraordinary care and deference. Both are trained in theology–Walker a Seattle pastor with a specialization in Christian education, and Mansfield with a dual Master of Divinity (MDiv) from Princeton Theological Seminary (PTS) and Master of Social Work from Rutgers.

Though both are Protestant, the two have spent years immersing themselves in Orthodox theology and sacred art. Walker grew up surrounded by ancient Orthodox churches in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and brings personal familiarity with Eastern Christianity; Mansfield is in the process of Presbyterian ordination, and has studied patristics and Greek to engage deeply with early Church sources.

What began as personal admiration developed into a deep research investigation when Mansfield and Walker learned the widow was never formally recognized as a saint. Despite her brief Gospel appearances, their first investigations revealed a trove of historical reverence.

“Why was she never canonized when other saints have much less scriptural narrative, patristic references, and fewer iconographic representation, but are still regarded as saints?” Mansfield asked.

“This is the driving force of our search,” Walker said. “How do we explain what appeared to just be an oversight?”

Though the woman’s name is not recorded in the biblical text, Mansfield and Walker refer to her as “Saint Kenosia,” drawing from the doctrine of kenosis, the self-emptying humility of Christ described in Philippians 2.

According to Church Fathers like St. John Chrysostom, this widow too “emptied herself” not only of her coins but of her entire livelihood, quietly foreshadowing Christ’s own sacrifice only a few days later. St. John Chrysostom used the term “kenosis” to describe her act of self-emptying.

“It’s a very uncommon word to use,” Mansfield explained. “It’s almost exclusively used for Jesus, so the fact that it’s used to describe her act, particularly given that it took place three days before Good Friday, is extraordinary.”

Despite centuries of liturgical, theological, and iconographic acknowledgment, the woman has remained unnamed and uncanonized. Mansfield and Walker’s work seeks not to introduce something new, but to draw attention to a deep and rich tradition.

Mansfield and Walker also observe that many early saints received names retroactively–St. Photini, the Samaritan woman at the well (John. 4:5-42), St. Veronica, the woman with the issue of blood (Matthew 9:20-22, Mark 5:25-34, Luke 8:43-49), and St. Dismas, the penitent thief crucified with Christ (Luke 23:39-43), are all examples.

“The tradition of bestowing a name is not about fabrication but veneration,” Mansfield said. “That was a very important part of the tradition that wouldn’t have been understood as false.”

Though unprecedented, the name Kenosia signals a theological truth: that this woman’s self-offering mirrors Christ’s own self-emptying love.

Mansfield and Walker’s research uncovered evidence that the woman was never forgotten by the Church (like saints such as St. Phanourios the Newly-Revealed), but merely overlooked in the formal processes of sainthood.

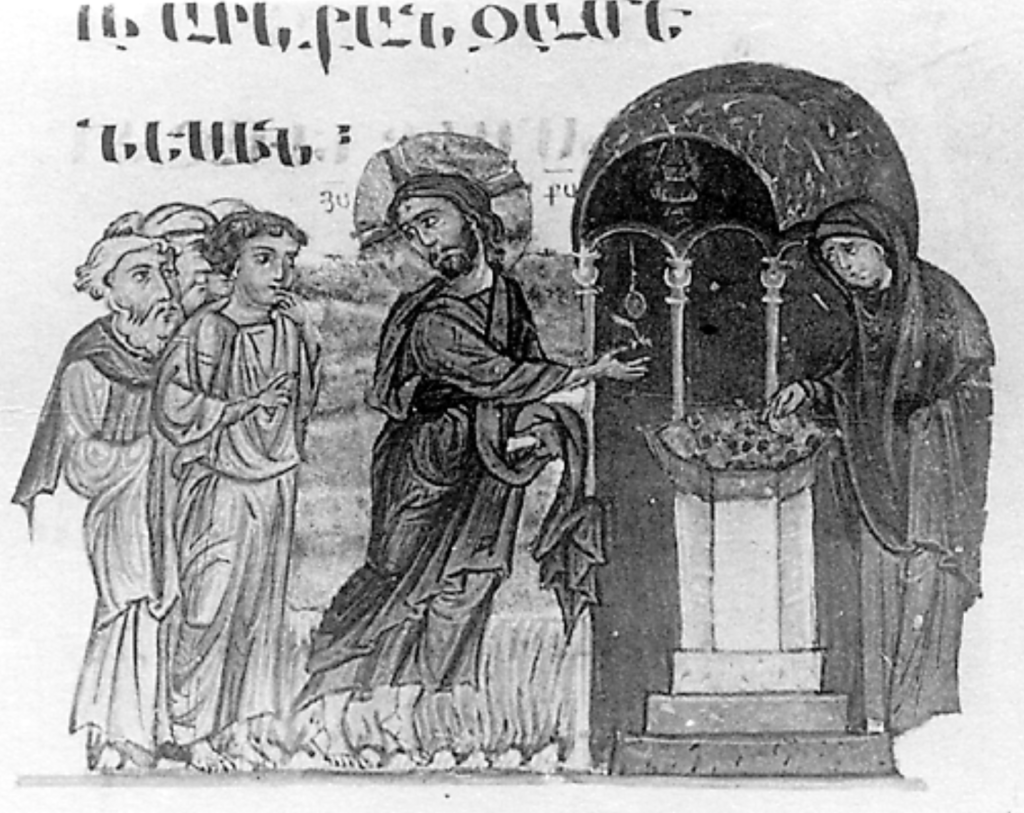

She appears in 6th-century Ravenna mosaics, Gospel illuminations, and wall frescoes in a posture of humility before Christ, with a temple offering box between them.

She is consistently featured in lectionaries and is venerated in the Alexandrian and Coptic liturgical traditions with figures like Abel, Abraham, and Zacharias. In Ethiopian rites for ordaining deaconesses, she is named among the holy women alongside the Theotokos and St. Mary Magdalene; ancient liturgies, such as those attributed to St. Mark, reference and uplift her offering.

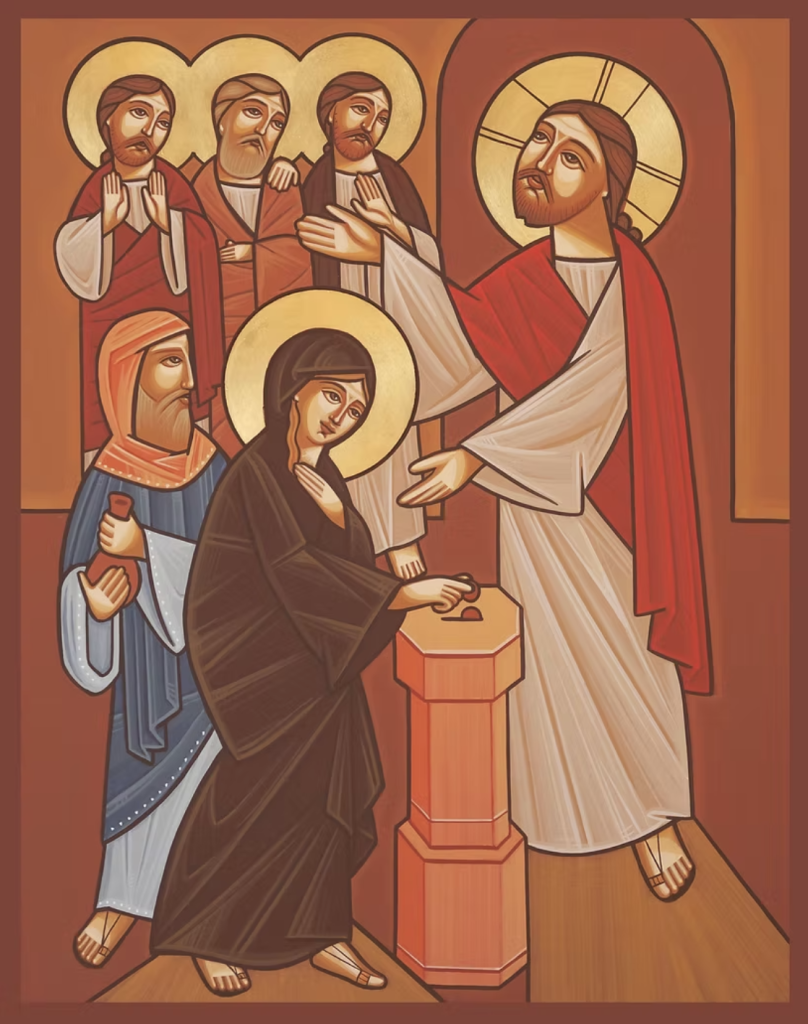

Traditional iconography does not depict her with a halo. However, one Coptic iconographer, Fadi Mikhail, chose to break with convention.

When Mansfield and Walker asked why he gave her a halo, Mikhail simply said, “Christ himself acknowledged the woman’s saintliness. Who then are we to deny this?”

This response captures the spirit of Mansfield and Walker’s work as well: they are not making a claim to ecclesial authority, but recognizing the beauty and sanctity already affirmed by Christ.

Their methodology reflects this humility. Instead of drafting a hagiography in isolation, they have sought counsel from Orthodox bishops, scholars, iconographers, and laywomen’s networks such as Axia Women. They have consulted with experts like Dr. Susan Ashbrook Harvey and clergy within both the Greek and Coptic Orthodox traditions.

Their aim is not to impose, but rather to listen and provide their research to the relevant communities, helping gather the theological, liturgical, and communal case for canonization from the ground up. Mansfield and Walker’s work echoes broader conversations about how canonization can reflect not just hierarchical decisions, but grassroots movements of reverence.

> Watch: Archbishop Elpidophoros speaks about the canonization of St. Iakovos of Evia

Canonization in the Orthodox Church has always begun organically, through local veneration by faithful. Communities remember, venerate, and uplift those whose lives reveal holiness, and only then do bishops formalize the recognition that has arisen organically among the faithful.

Mansfield and Walker are careful to honor this reality. Their research does not presume authority, but simply gathers the evidence so Orthodox communities can discern for themselves whether this is someone they wish to elevate.

The recent canonization of St. Olga of Alaska by the Orthodox Church in America serves as an encouraging precedent, emerging largely through women’s devotional groups. In the same way, any movement toward recognizing Kenosia must come from the Church’s own communities, whose lived reverence gives rise to official recognition.

At a time when many are burdened by materialism, inequality, and disconnection from spiritual heritage, Kenosia offers an image of radical trust, humility, and sacrificial love. She challenges modern assumptions about worth and wealth, and invites all Christians, Orthodox or otherwise, to consider what it means to give everything we have.

Her story, like the coins she gave, may be small in the world’s eyes, but its value in the eyes of the Lord is immeasurable. In honoring Kenosia, the Church has an opportunity to uplift the witness of poor and marginalized women, and celebrate the quiet holiness that has always existed at the heart of the Christian story.

Through their reverent, reflective, and deeply communal work, Mansfield and Walker are offering not just a proposal for canonization, but a testament to the enduring power of the saints and the communities who remember them.

The post These scholars aim to canonize the woman they call ‘Kenosia’ appeared first on Orthodox Observer.